KAIUMALO

Kaya Agari

Solo show

Curated by Paula Borghi

KAIUMALO

‘There is a world in each person’, as Clarice Lispector once wrote. However, it is not impossible to see some similarities between worlds, depending on the culture in which they are integrated. Thus, when you enter the world of Kaya Agari, you also enter the Kurâ-Bakairi way of life, her ethnic group. In order to better familiarize myself with her universe, in May this year I spent 12 days in the Kuiakware village and 3 days in the city of Cuiabá, both in the state of Mato Grosso, where the artist lives with her family.

Kaya was born in Cuiabá General Hospital in 1986, growing up in Pakuera village, the head village for the Kura people. From 2001 to 2008 she lived in the city of Cuiabá to study, later returning to the indigenous territory in the Kuiakware village, founded in 2004 by her grandparents. In 2012 she returned to the capital with her brother Jeferson Agari, both entering UFMT university. In the city she lives with her husband Elmir Aiakamyna, son Kauã Tawagy and daughters Luma Kawyru, Malu Kaya and Luara Atawy. His grandfather Carlos Taukane, mother Maisa Taukane, father Laércio Agari, brothers Felipe Agari and Jeferson Agari and their families live in the village. This is where her whole family gathers on vacations, festivities and whenever possible, where the artist has her own home, made from the clay walls of the house of Bráulio Apy, her husband's grandfather, with the wood from the house of her grandmother Vilinta Kaiumalo, the first house in the village, and the floor laid by her late uncle Nilton Maetawa. This is an âtâ (house) built by many hands, overflowing with stories and love.

Located in the Bakairi Indigenous Land, 100 km from the headquarters of the municipality of Paranatinga, the Kuiakware village is in a territory with nine other villages spread over an area of around 62,000 hectares of the Cerrado biome. The territory originates from the resistance of the Kurâ-Bakairi, who around the 18th century were expelled from their place of origin, the Salto Sawâpa, by the violence of colonizers and enemy indigenous peoples. Located in the municipality of Boa Esperança, also in Mato Grosso, Salto Sawâpa is an area fondly remembered by the old-timers as the “reign of the matrinchãs”, due to the abundance of food this fish offered.

The diaspora of the Kurâ-Bakairi people caused them to migrate in three different directions, directly affecting their subsistence and history. As anthropologist Edir Pina de Barros says in her book “Os filhos do Sol” (The Children of the Sun), one group moved to the headwaters of the Arinos River and became involved in mining activities, another (which also includes Kaya's family) went to the upper Paranatinga River and became involved in farming and cattle raising, and the largest group went to the upper Xingu River, a region known as the first indigenous land approved by the federal government.

The Bakairi Indigenous Land is surrounded by two large units of Brazil's biggest agricultural producers, the Vanguarda Group and Bom Futuro. The latent presence of agro-business in the territory makes it the main economic reference for the village, which ranges from renting land to raise cattle or plant monocultures, to providing services for neighboring farms. As a result, the territory's soil is already showing signs of erosion and the rivers are being polluted by pesticides from the commodity crops that are spreading more and more in and around the village. Since 1980, agro-business has been mainly responsible for contaminating and poisoning the region's main river, the Paratininga in Portuguese and Pakuera (River of Pigeons) in the Karib language. Even in the face of all the adversities, this is still a fishing river for the Kurâ-Bakairi people, who maintain it as a symbol of the resistance of their culture.

Just like fishing, cultural events depend on the health of the territory, since everything is connected. The Buriti palm tree, for example, provides much of the raw material for rituals and the prayer house itself, which is made entirely from its straw. In the Kapa, a ritual usually promoted by singing and dancing in gratitude to nature, all the clothing is made from Buriti straw. For the ritual, the men's faces are covered by a kind of mask made from the strands of Buriti straw that goes down to their knees, covering their entire backs, over a skirt made from the same material. The arms are covered with green leaves from other trees. In August and September of this year, as a result of the drought and the criminal fires throughout Brazil (especially in Mato Grosso, the state that burned the most), the Kapa was danced to ask for rain.

During my stay in the village, I was able to follow a Kado, a ritual that includes a set of sacred or playful songs and dances. What I witnessed was a playful Kado called Iamurikumã, which means women's song and dance. The organizer was Maisa Taukene, who as well as being Kaya's mother is one of the main guardians of the Kurâ-Bakairi culture in her territory. At the time, she had been invited by the Atura village, next door to Kuiakware, to teach the women and girls how to sing and dance, as well as emphasizing the importance of body painting with graphic motifs.

Acting as a place of affirmation and resistance for indigenous peoples in the face of the countless forms of violence caused by systemic colonization, it is true to say that body painting marks and affirms the identity of indigenous peoples. During Kado, I remember Kaya's mother insisting that the younger girls paint their bodies in the traditional way; on the side of the body, from the waist to the ankle and not just to where the shorts cover, at thigh height. She reminded the younger girls that this painting made of graphics with natural paint was the first garment of her people, however ephemeral and immaterial it was; a concept further explored by Isabel Teresa Cristina Taukane, Kaya's cousin, in her doctoral thesis “Kurâ Iwenu (Our Painting): performance and resistance in Kurâ-Bakairi body painting”.

The Kurâ-Bakairi body paintings vary between men, women and children and are inspired by animals such as dragonflies, jaguars, anacondas, fish and tortoises, among others. As in many indigenous cultures, by dressing up in a particular body graphic, you become a little bit of that animal. In Brazil, body paint is usually made from jenipapo and applied with the stalk of a palm tree. However, nowadays, body painting doesn't follow such a rigid rule in terms of both the way (type of paint) and the use of images (referring to gender and age), even though ancestral memory continues to awaken in the skin the time when animals were people.

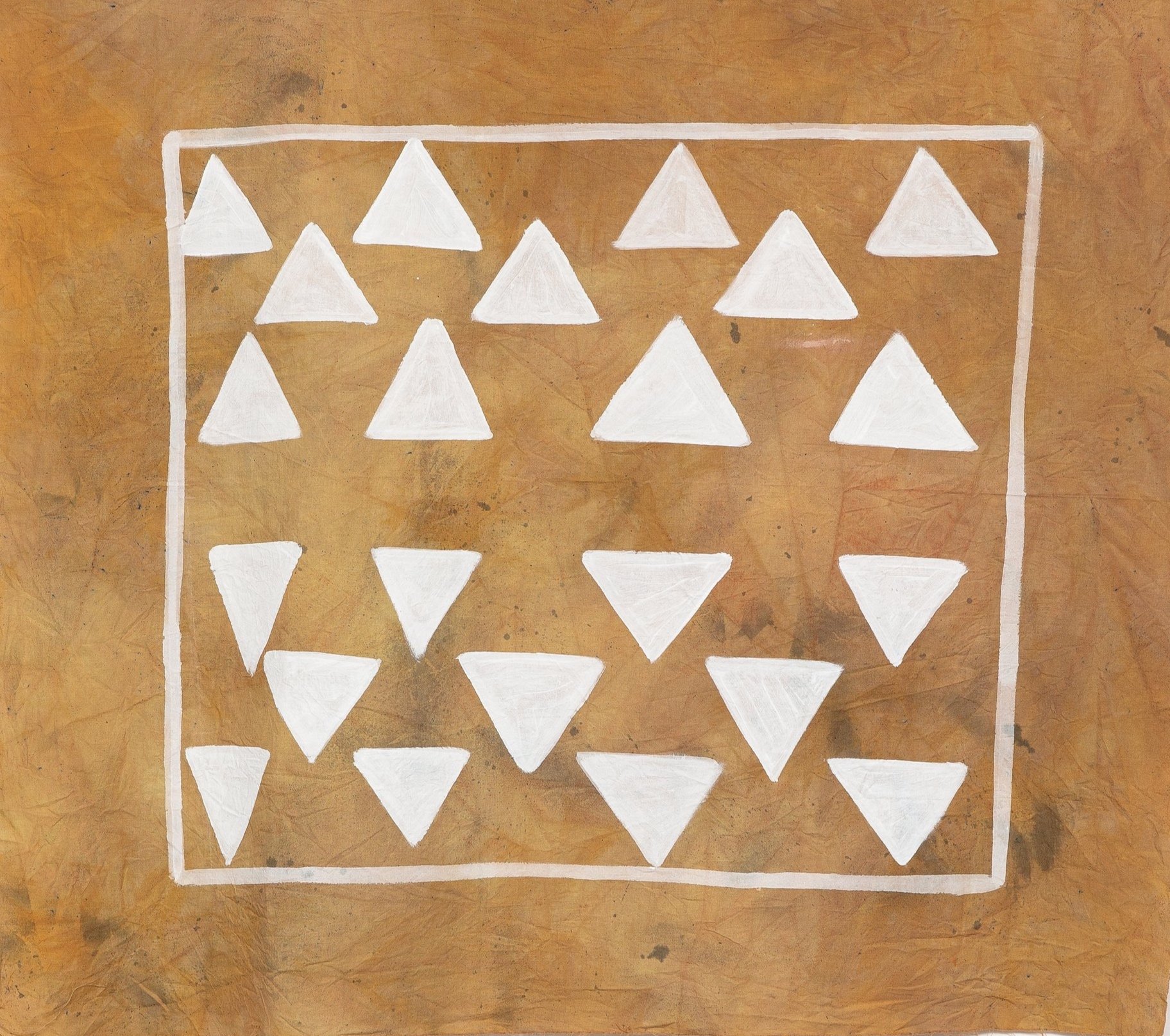

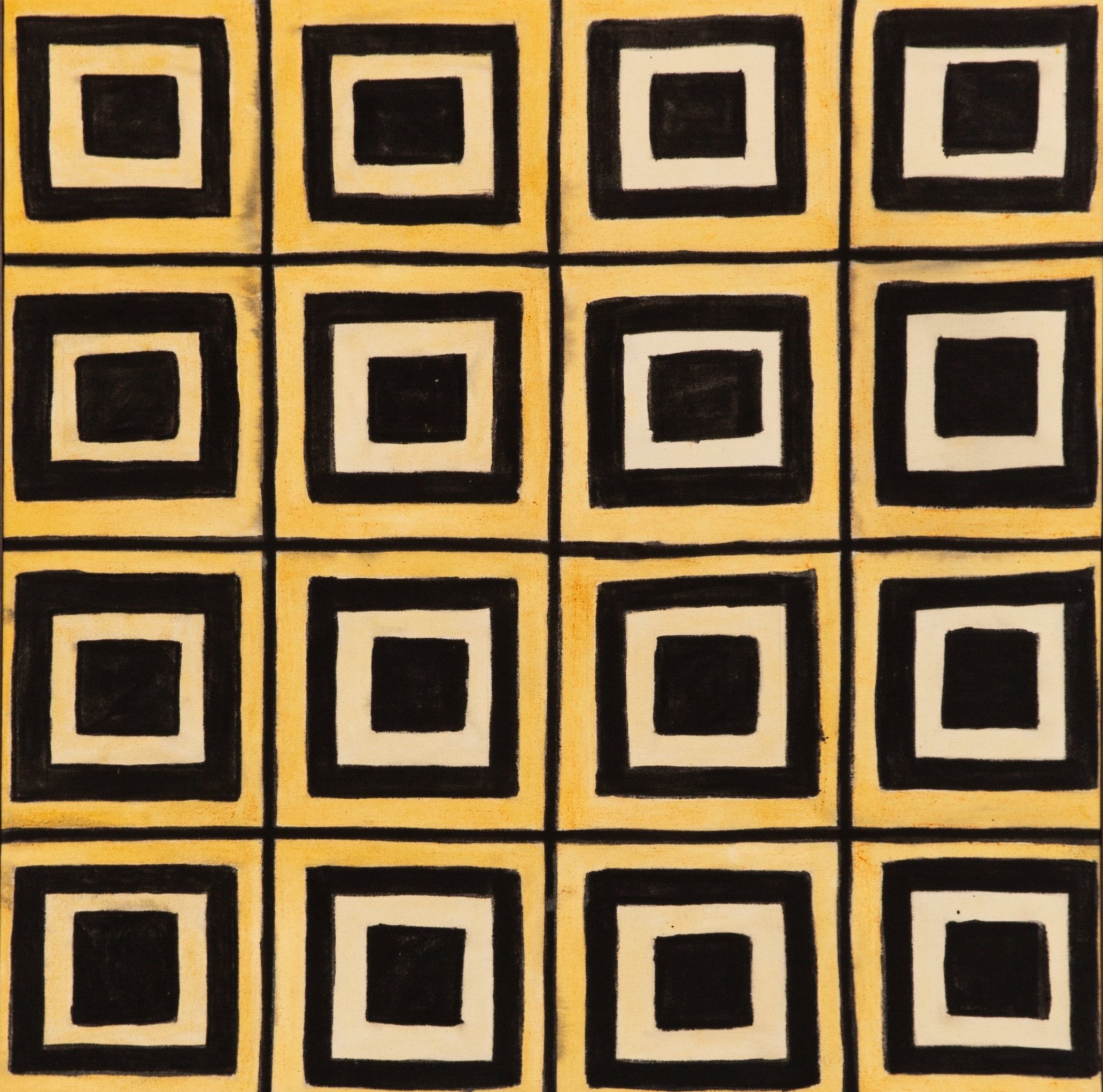

Thus, when we come across Kaya's graphics on cotton fabric, it is possible to interpret that the artist makes her paintings dress the walls of the “white cube” with the symbolic presence of animals, bringing a little hope of an ancestral future. In other words, it's as if her work performed a pictorial ritual for the eyes of those who inhabit the urban space, awakening in their unconscious the memory that one day the city was also a forest. This memory lives on, even though the concrete and asphalt make it fall asleep.

In the large-format paintings we have a combination of varied graphics that can be interpreted as alluding to the forest, a place where all the animals are together and mixed in the balance of life. And if in the forest we can often hear the animals, even if we can't see them, in the paintings we can metaphorically activate both sight and hearing through the symbolic representations of the graphics. It's as if the polyphony of graphics awakens a rhythmic pulse capable of evoking the presence of each symbolized animal. The visuality can be read like a musical score, in which each graphic corresponds to a sound. The smaller format paintings, on the other hand, work on the graphics individually, as if the animals were singing in a solo.

Presenting for the first time a video work and an installation, as well as three dresses, in these works Kaya brings out more explicitly the family dimension that is present throughout her production. Most of the time, the artist relies on her family for the creation of her artwork, in a relationship of mutual cooperation and knowledge that is passed down from generation to generation. But beyond the process, in these three works we can see the direct presence of family members in her visuals.

In the video, Kaya's mother prepares a tapioca pagu (porridge) on her wood stove, while speaking in her language, Karib, about the role of the gourd and porridge in Kurâ-Bakairi culture. Porridge comes from a knowledge that was taught by his mother's mother and so on; it is the preparation of a food that the whole village knows about, as well as many other indigenous peoples, just like graffiti. After cooking, the porridge is served in a gourd made of calabash, the fruit of the Lagenaria plant which is used as a gourd in different cultures around the world.

As Kaya's mother puts it, the gourd is used for many things in Kurâ-Bakairi culture, such as drinking water, eating porridge and even feeding the recently dead spirits. It is also an element often used in wedding rituals. Those getting married drink the porridge in the gourd and share it with their in-laws to seal their marriage. It is a food and a way of serving it that comes from collective, ritualistic and spiritual knowledge.

Therefore, in her first solo show, we are invited to enter the Kurâ-Bakairi cosmologies and the world of Kaya Agari, who opens the doors of her house, introduces her family and shares her porridge with us. It's no coincidence that the exhibition bears the surname of her ningo (grandmother) Vilinta Kaiumalo (26/07/1938 - 25/12/2023), who, although no longer on earth, is still very much alive in the history of Kaya's family. So this is a tribute to her and also a way of materializing her physical presence in the exhibition, as well as the presence of all the artist's maternal relatives. There are three dresses here that correspond to three generations: one of Kaya's, one of her mother's and one of her grandmother's, all painted by Kaya and sewn by her mother.

In the installation, gourds with the names of the artist's maternal family are arranged on the wall like a family tree, with the oldest at the top and the youngest below. The work is based on a decoration that was in the artist's house in the village, in which the names of her family (husband, son and daughters) were written on the gourds and arranged in line on the clay wall. From this image came the provocation for Kaya to bring to the exhibition space something that is so typical of her world, like the dresses, the porridge and the graffiti painting itself. The installation with the gourds is a response to this provocation, but it is also a way of bringing all of Kaiumalo's descendants to take part in this exhibition held in his honor.

So Kaya reminds us that even though this is a solo exhibition, she will always be accompanied by her grandmother and all her ancestral and contemporary relatives. That her artistic work is also collective. That her universe, as unique and non-transferable as it is, is crossed and constituted by an even larger one: the Kurâ-Bakairi world.

Paula Borghi

São Paulo, 2024